“Through realism, Gissing exhibits both sides of a cultural shift, with depictions of a man weathered down by metropolis living in New Grub Street (1891), and a yearning for a simpler time with The Private Papers of Henry Ryecroft (1902).”

This is a continuation from my introductory blog post, in which I presented my preliminary findings and thoughts on my area of research concerning the so-called ‘Russian Influenza’ outbreak, which you can read here. While this post touched on accessibility to healthcare, another major public health issue is housing, and specifically the regulations around housing during an epidemic.

In George Gissing’s New Grub Street (1891), Edwin and his wife Amy worry about rent a lot; their first discussion happens in Chapter IV and continues throughout the novel, with Edwin understanding that he cannot support his family whilst in poverty:

He knew what poverty means. The chilling of brain and heart, the unnerving of the hands, the slow gathering about one of fear and shame and impotent wrath, the dread feeling of helplessness, of the world’s base indifference. Poverty! Poverty!1

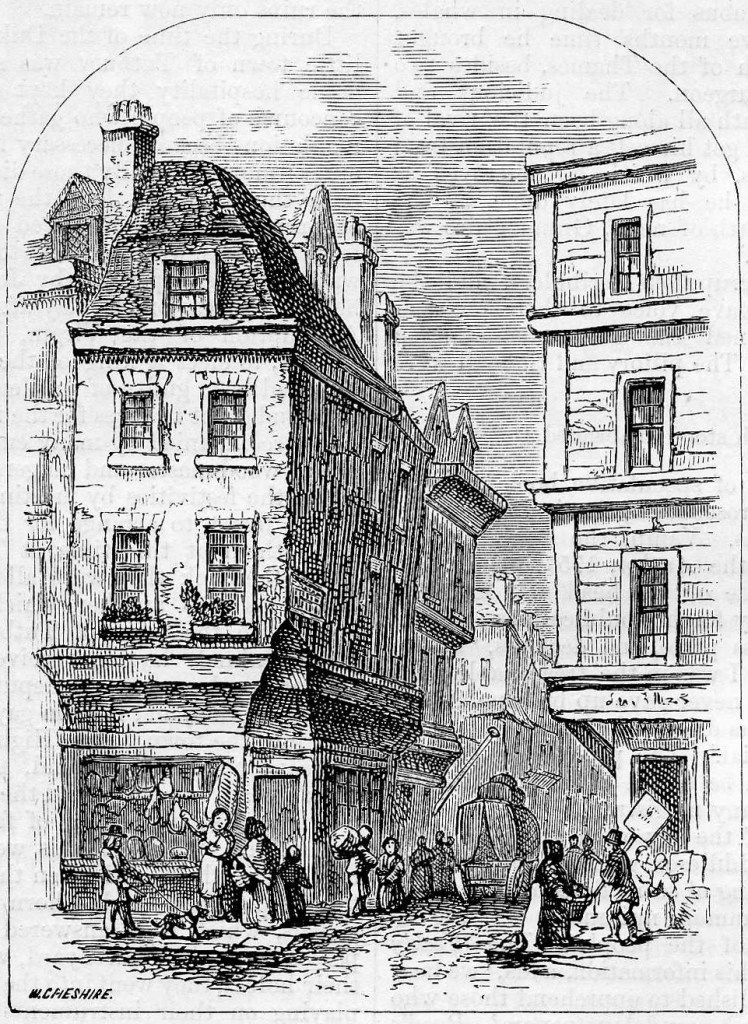

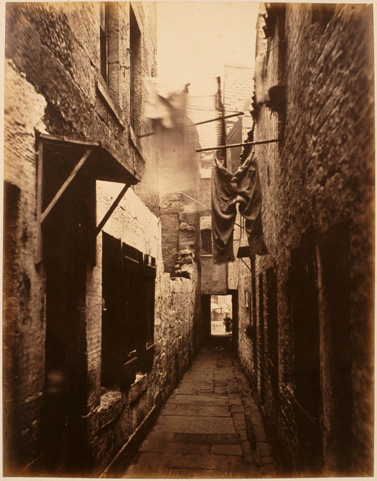

During the Victorian era, new policies were made in the name of sanitary and social reform, but the persistent problem was that paupers were being displaced in order to make way for new streets and to encourage better air circulation in an effort to combat diseases.2 Over the course of thirty years towards the latter half of the century, you can find reforms such as the Sanitary Act of 1866 (criminalized overcrowding), the Artisans’ and Labourers’ Dwellings Act of 1868 (local authorities could now condemn and destroy insanitary housing), amongst others. While these were made slightly earlier than the period of the Russian Influenza, M. J. Daunton notes that attitudes on slums and “plague spots” were dominant up until the end of the century.3 Of course, one would not actively choose to be situated in a slum, due to their overcrowded nature and renown as plague spots.

With these actions in mind, a clear understanding of the difficult situation of the displaced forms, as they could not afford rent in other areas. Furthermore, existing dwellings that paupers could afford were terrible, yet those enacting sanitation policies believed that the reason disease was strife in these areas was due to “personal morality”, and that the poor needed to be taught sanitation, rather than acknowledge the fact that poor housing was often due to poverty.4

These housing regulations also bring attention to a class divide, where middle and well-to-do people were making rules and regulations regarding the lower classes, whilst not understanding how poverty and being financial instability worked. Poor people do not get sick on the basis that they had a lack of morality, as many Victorian commentators speculated. Instead, it stemmed from a lack of resources and funds to live a life where they did not have to live in bad housing and could afford a doctor and medication, amongst other things like proper shelter, and decent food. New Grub Street constantly reminds us of the fragility of the human body when put under such stress, that “half-year of insufficient food and general waste of strength would make the coming winter a hard time for him, worse probably than the last”.5 In Gissing’s novel, the protagonist Edwin is not a man ‘lacking in morality’, nor does he do anything like excessive drinking or gambling; he puts in substantial effort to ensure that he secures a job with a regular wage so that he can afford to live. This would significantly contribute to Edwin’s decision to take up his post at Croydon – not only would he get a stable wage, but he would get a place to live, one that would be better than his living situation in the metropolis – “a dwelling rent free, and a hundred and fifty pounds a year”.6 This is important because it meant that he had far fewer worries about housing and could spend the money that he would have spent on rent on other things, like sufficient food.

Everything Falls Apart – Deterioration and the Fin de Siècle

While these reforms were made in mind to keep disease at bay, it also dealt with notions of pauperism, decency, and morality (or lack of). This “deterioration of the environment” is why well-to-do classes, who were in positions of authority, wanted to do a systematic eviction of paupers in their neighborhoods; with disease and sin having a strong relationship in the cultural consciousness, this was something that was to be avoided.7 This is the fin de siècle – the world is falling apart. Everything is deteriorating.

It would also make sense that the population would get overwhelmed with the onslaught of new information – things were moving at a speed that was never seen before, as represented not only by the mainstream press, but also by medical journals. William Squire wrote in the Lancet that “[s]o it was in most of the capitals of Europe; no sooner had a telegram announced the absence of this epidemic than we heard of it[s] attacking the postmen, the railway servants, or the barracks”.8 This anxiety of the world deteriorating stems from the influenza attacking those deemed “most essential to the smooth functioning of the economy” and society as a whole.9 The feeling was further agitated by a large number of members in government falling ill, as well as the death of the Duke of Clarence and Avondale, recorded in the Lancet.10

Having public servants, in actuality and in fiction, succumb to illness significantly contributed to the general sphere and tone of the fin de siècle, as it represented cultural anxieties of rapid urbanization and speed of social change. Through realism, Gissing exhibits both sides of a cultural shift, with depictions of a man weathered down by metropolis living in New Grub Street, and a yearning for a simpler time with The Private Papers of Henry Ryecroft (1902).11 These two novels, while not presenting similar storylines, provide different currents of thought within the same period in which the influenza epidemic in question was a pertinent topic.

Rural and Urban Experience in Gissing’s Realist Fiction

Ryecroft’s lamentations on science and slow living in the countryside contrasts sharply against Edwin’s general illness and living struggles in the city in New Grub Street, which creates an opportunity to reason with the anxiety of urbanization. Consider this passage:

‘The exquisite quiet of this room! I have been sitting in utter idleness, watching the sky, viewing the shape of golden sunlight upon the carpet, which changes as the minutes pass, letting my eye wander from one framed print to another, and along the ranks of my beloved books. Within the house nothing stirs. In the garden I can hear singing of birds, I can hear the rustle of their wings. And thus, if it please me, I may sit all day long, and into the profounder quiet of the night.’12

Whilst Ryecroft is noted to be “a struggling man, beset by poverty and other circumstances very unpropitious to mental work”, this is living that is nowhere near the “stressful urban lifestyles” that many people lead in the city, and it is nowhere akin to the psychological stress that Edwin Reardon suffers through when he has to constantly consider job prospects, living situations, and health, which are all linked to his difficult tenure in London.13

“Stressful urban lifestyles” brought on overworked professionals; New Grub Street provides ample examples, such as “[o]ther men have worked hard in seasons of illness; I must do the same”, as well as attempting to “at least give faithful work for his wages until the day of final breakdown”, all leading back to the fact that he could not afford (in a financial sense) to take a day off (this point has been touched on in my last post).14 This was not a strange phenomenon, as long hours during the holiday season meant postmen and railway services were affected, as well as doctors who were subjugated to “the extra work thrown upon them during the epidemic”.15 When this is coupled with the aftereffects of influenza such as “depression”, “great languor” and “self-destruction”, it provides an onset of waste; men, body and mind, are wasting away.16

The influenza, through my study, spreads its influence much akin to a web; it finds itself in fiction, in newspaper articles, medical journals, advertisements, housing reforms, and a cultural phenomenon that scholars later on would perceive as defining the fin de siècle. It is fascinating to see how disease affects all facets of life – so often are epidemics obscured by facts and figures of casualties that we tend to forget how people interacted with the illness. People bemoaned and people studied and people lived. History just repeats itself, over and over again.

Ching Chi Chan

Ching Chi Chan is a third year within the Bachelor of Advanced Humanities, studying English Literature. She joined the UK Media and Epidemics team for a short period of six weeks under the supervision of PI Melissa Dickson as a recipient of a Summer Research Scholarship from the University of Queensland, Australia.

You can find Ching Chi’s Meet the Team blog here.

- Gissing, George. New Grub Street. Oxford UP, 2016 (p. 60). ↩︎

- Daunton, M. J. “Health and Housing in Victorian London.” Medical History, vol. 35, supp. 11, 1991, pp. 126–144, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/medical-history/article/health-and-housing-in-victorian-london/FE7A611363D25E5AA1E32DF6AC7CBE6C (p. 136). ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 139. ↩︎

- Ibid., pp. 138-39. ↩︎

- Gissing, New Grub Street, p. 323. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 307. ↩︎

- Cooley, Charles Horton. “An Organic View of Degeneration”. Social Process. Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1918, pp. 153-168 (pp. 157, 153). ↩︎

- Squire, William. “The Infection of Epidemic Influenza.” The Lancet, 1890, vol. 135, no. 3477, pp. 843-844, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)19721-2 (p. 843). ↩︎

- Honigsbaum, Mark. “The Great Dread: Cultural and Psychological Impacts and Responses to the ‘Russian’ Influenza in the United Kingdom, 1889–1893.” Social History of Medicine, vol. 23, no. 2, 2010, pp. 299–319, https://doi.org/10.1093/shm/hkq011, (p. 316). ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 310; “The Death of The Duke of Clarence and Avondale.” The Lancet, vol. 139, no. 3568, 1892, pp. 146-150. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)12271-9, (p. 146). ↩︎

- Gissing, George. The Private Papers of Henry Ryecroft. Constable and Co., 1903. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 6. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. viii; Honigsbaum, p. 989. ↩︎

- Gissing, New Grub Street, pp. 116, 313. ↩︎

- Squire, p. 844. ↩︎

- “MEDICAL SOCIETY OF LONDON.” The Lancet, vol. 138, no. 3564, 1891, pp. 1392-1394, ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)05017-1, p. 1394. ↩︎