“This was the time where Pfeiffer’s bacillus was heavily discussed in relation to influenza, yet in both fiction and primary sources, you find people not wanting anything to do with it.”

What are the main epidemics that your team focuses on?

I am a third year within the Bachelor of Advanced Humanities, studying English Literature. I joined the UK Media and Epidemics team for a short period of six weeks under the supervision of PI Melissa Dickson as a recipient of a Summer Research Scholarship from the University of Queensland, Australia.

We are focused on the Russian Flu, otherwise known as the 1889-1890 pandemic.

What have your key research question(s) been this month?

The Summer Research Scholarship team has been tasked with questions surrounding the Russian Flu, and notions such as science fiction, and children (find the other posts from our team, Susan Sudbury and Lily Burke).

Personally, I am looking at the way social classes, especially those in the working and lower-middle classes, interacted with the flu. This then led to the development of subsequent questions on healthcare and the fin-de-siècle phenomenon.

The fin de siècle (translation: end of century) marks the end of the 19th century and the turning of the 20th. This was a time of a significant cultural shift, where significant progress towards modernity is imbued with anxieties of the future, a mentality of perceiving the end. It is widely seen as a period of degeneration, pessimism, and decadence.1

A piece of literature that I am focused on to help draw out class analysis is George Gissing’s 1891 novel, New Grub Street. I am concerned with literary depictions of influenza; why was it used? Why is it that only Edwin (the story’s main character) dies of influenza, despite the disease being known as indiscriminatory? What can it tell us about the social and historical context? How does this gear up towards the fin de siècle? I am currently reading and thinking about another Gissing novel, The Private Papers of Henry Ryecroft (1902), to hopefully do a side-by-side comparison of social class, illness, and the fin de siècle.

Do you have any images which resonate with your research that you would like to share?

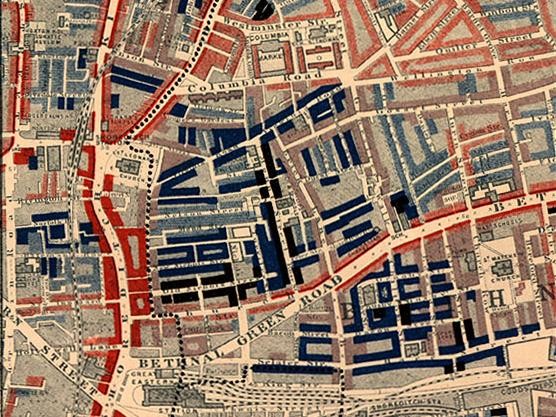

This is part of Charles Booth’s poverty map showing the Old Nichol, a slum in the East End of London. Published 1889. Red was “well-to-do”, light blue “poor”, and dark blue “very”. Poverty and poor sanitary conditions caused illness to be rife.

Have you found any key differences between how the epidemic disease experiences of marginalised or minority individuals, and between those of the general population, have been communicated?

The major marker, I believe, is access to healthcare. The healthcare system was “decentralized, inefficient, and inegalitarian, with considerable competition within and between the public and private sectors”. This demonstrates class disparity. While the middle and upper classes received care at home, the poor were filtered into two types of institutions: workhouses for paupers and voluntary hospitals for the deserving poor.2

But take Edwin Reardon from Gissing’s New Grub Street; he did not receive any care for his bouts of colds and influenzas until the very end of the book, and he then subsequently dies. He works his clerk job at the hospital and refuses to take leave, which is important to note as “[n]on-established staff received no sick pay. Many ‘carried on’ for fear of losing their wages”.3 Due to how the healthcare system was set up, money was a significant factor – if the choice was between being sick but able to afford rent, or not having money because you stayed home, and then not having a place to live because you can’t pay rent, it would suffice to say that Edwin had reason to go work. It is also disheartening to see that things haven’t changed that much from the past…

To what extent have you found that differing technologies can change how epidemics have been communicated? Are there any particular technologies that you wish to highlight?

Not necessarily technologies, but what is interesting is a disinterest towards science during a time where they have seen great advancements in medicine, in science, as well as coming off the Industrial Revolution (late 18th century to mid-19th century). This was the time where Pfeiffer’s bacillus was heavily discussed in relation to influenza, yet in both fiction and primary sources, you find people not wanting anything to do with it. In New Grub Street, someone mentions that they don’t want to read about vaccines, and in Henry Ryecroft, the titular character makes his stance abundantly clear that as he “glance[s] down the waste print, one word catches my eye again and again. It’s all about “science” – and therefore doesn’t concern me”.4 The editor of the Lancet writes about the public’s refusal “to take the same precautions” and that there is “carelessness with regard to risks of infection”.5

Perhaps, though, they were so fatigued with the changing environment and exhaustion from overworking (especially the working class) that new developments aren’t the main priority. After all, one cannot be expected to take necessary precautions if one cannot afford to live – it’s hard to pay attention to new things when everything you knew of in the world around you is falling apart.

What has been your most surprising finding while working on the Media and Epidemics project?

There is this link between the fin de siècle and the influenza epidemic that I am trying to sink my teeth into; the degeneration, bouts of sickness that lead to chronic fatigue… While I haven’t got a nice, concrete answer yet, I don’t think it is too off the mark to have recently experienced a pandemic and a shift in thought; having seen how society got warped through COVID-19, I think there is something to be said about there being a pattern.

I was also surprised to learn that people in general saw influenza as “a minor illness”6, which led to some unconventional cures, such as this:

- Martens, David. “Fin de siècle.” Routledge Encyclopedia of Modernism, Taylor and Francis, https://www.rem.routledge.com/articles/fin-de-siecle. ↩︎

- Hollingsworth, J. Rogers. “The Delivery of Medical Care In England And Wales, 1890-1910.” Madison: Institute for Research on Poverty, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1980, https://www.irp.wisc.edu/publications/dps/pdfs/dp61480.pdf, p. 1, 5. ↩︎

- Gissing, George. New Grub Street. Oxford UP, 2016, p. 312; Smith, F. B., “The Russian Influenza in the United Kingdom, 1889–1894.” Social History of Medicine, vol. 8, no. 1, April 1995, pp. 55–73, https://doi.org/10.1093/shm/8.1.55, p. 59. ↩︎

- Gissing, George. New Grub Street, p. 276; Gissing, George. The Private Papers of Henry Ryecroft. Constable and Co., 1903, p. 287. ↩︎

- “The Death of The Duke of Clarence and Avondale.” The Lancet, vol. 139, no. 3568, 1892, pp. 146-150. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)12271-9, p. 147. ↩︎

- Smith, F. B., “The Russian Influenza in the United Kingdom, 1889–1894”, p. 67. ↩︎