“Given how central metaphor is to how we conceptualise the world, it was inevitable that metaphor would play a pivotal role in our understanding of the COVID-19 pandemic.”

This blog post begins with a brief introduction to conceptual metaphor theory, then outlines how the COVID-19 pandemic was both understood through metaphor (and became a metaphor through which other concepts could be understood), before exploring how artistic responses to COVID-19 and illness engage with their subject matter through metaphor.

Conceptual Metaphor Theory

Metaphors We Live By saw George Lakoff and Mark Johnson argue that ‘our ordinary conceptual system, in terms of which we both think and act, is fundamentally metaphorical in nature’.1 Central to this argument was the discovery of conceptual metaphors—metaphorical patterns of thought defined by ‘a systematic set of correspondences between two domains of experience’.2 Conceptual metaphors comprise a target domain (the domain that is being understood) and a source domain (what the target domain is being understood in terms of).

The existence of conceptual metaphors is betrayed by the linguistic metaphors that we use in everyday discourse. We can examine what our metaphorical conceptual system is like by looking at the metaphorical language that we use, since it is rooted in the same metaphorical concepts that structure our thought. For example, the conceptual metaphor TIME IS A VALUABLE RESOURCE/MONEY manifests in linguistic metaphors like:

You’re wasting my time

You cost me a year of my life

I feel like I’m living on borrowed time

The treatment will buy me some time

What is most striking about these examples is that, though we deploy them unthinkingly, they speak to an underlying systematicity and logic.

Paul Thibodeau and Lera Boroditsky (2011) ran an experiment in which two sets of students were asked to read a report about crime. The first set read a report where crime was described as a ‘beast preying’ on the city. The second set read a report where crime was described as a ‘virus infecting’ the city. The reports were otherwise identical. When asked to propose solutions to the problem of crime, 71% of the participants who read the former called for more law enforcement, compared to 54% of the participants who read the latter.3 Participants who read that crime was a virus were more likely to suggest social reform. However, when asked to explain their reasoning, very few participants identified the metaphors used to describe crime as influential when it came to proposing solutions, suggesting that metaphors can exert a strong yet covert influence over how people attempt to solve complex problems.

COVID-19 as Target Domain

The language used to describe the pandemic at its outbreak could not have been more warlike. President Trump, for example, described himself as a ‘wartime president’, the virus. as an ‘invisible enemy’ and, referring to the factory workers of the Second World War, spoke of the need to make ‘shared sacrifices for the good of the nation’.4

The PANDEMIC IS WAR conceptual metaphor, whilst initially dominant, driving much of the metaphoric discourse, decreased in usage sharply, whilst metaphors of cohabitation (‘we must learn to live with the virus’) increased. By October 2021, war and cohabitation metaphors were appearing at the same rate.5

But what caused the decrease in war metaphors? One possibility is the negative implications of following the metaphors to their logical conclusion, known as their ‘metaphorical entailments’—war framings could be seen to justify authoritarian interventions, and further imply that those who died did not fight hard enough.6

The #ReframeCovid project, of which Elena Semino was a part, saw metaphor researchers crowd-source metaphors for the pandemic with a view to compiling alternatives to the PANDEMIC IS WAR metaphor. Forest fire metaphors were pinpointed as being particularly apt. As a source domain, a forest fire is ‘widely accessible, well-delineated and image-rich’ and ‘precise and clearly applicable mappings’ exist between it and the pandemic as target domain.7

Forest fire metaphors can, for example, elucidate how measures for reducing infection work (much like how fire breaks are cut through forests, contact between people can be reduced to starve the metaphorical fire of fuel), create links between health inequality and pandemics (people living in cramped, unsanitary conditions are even more vulnerable, much like how those living in low-quality housing are more susceptible to the effects of fire) and help to imagine a future post-pandemic (just as much of the work to stop the spread of forest fires happens before they arise, we should invest time and resources to combat the conditions which give rise to pandemics).

COVID-19 as Source Domain

When looking at Arab political cartoons, Ahmed Abdel-Raheem found that the COVID-19 pandemic, with all its associated images and actions (getting vaccinated, facemasks, lockdowns, etc.) became a rich cradle of source domains with which to interpret and understand topical issues.8

In one cartoon by Hani Abbas, for example, the logos of social media platforms are presented as viruses coming from a mobile phone. The phone is clutched in the hand of a man wearing a facemask which has the word ‘block’ written on it. Social media, then, becomes a harmful virus, the effects of which can be reduced by individuals blocking the offending websites. Following the logic of the metaphor further, the suggestion is that the harm that social media causes to individuals can be transmitted to others, and that it is our duty as concerned citizens to guard against this transmission.

Another cartoon, by Muhammad Sabaaneh, depicts a syringe, inside of which is a Palestinian with a slingshot. The caption (‘A vaccine against the occupation’) redoubles the notion of Isreal’s occupation as a virus, and armed resistance as a vaccine against it. Abdel-Raheem concludes that the pandemic changed the way we see the world—that appropriating it as a metaphor ‘imposes horror on other things’.10

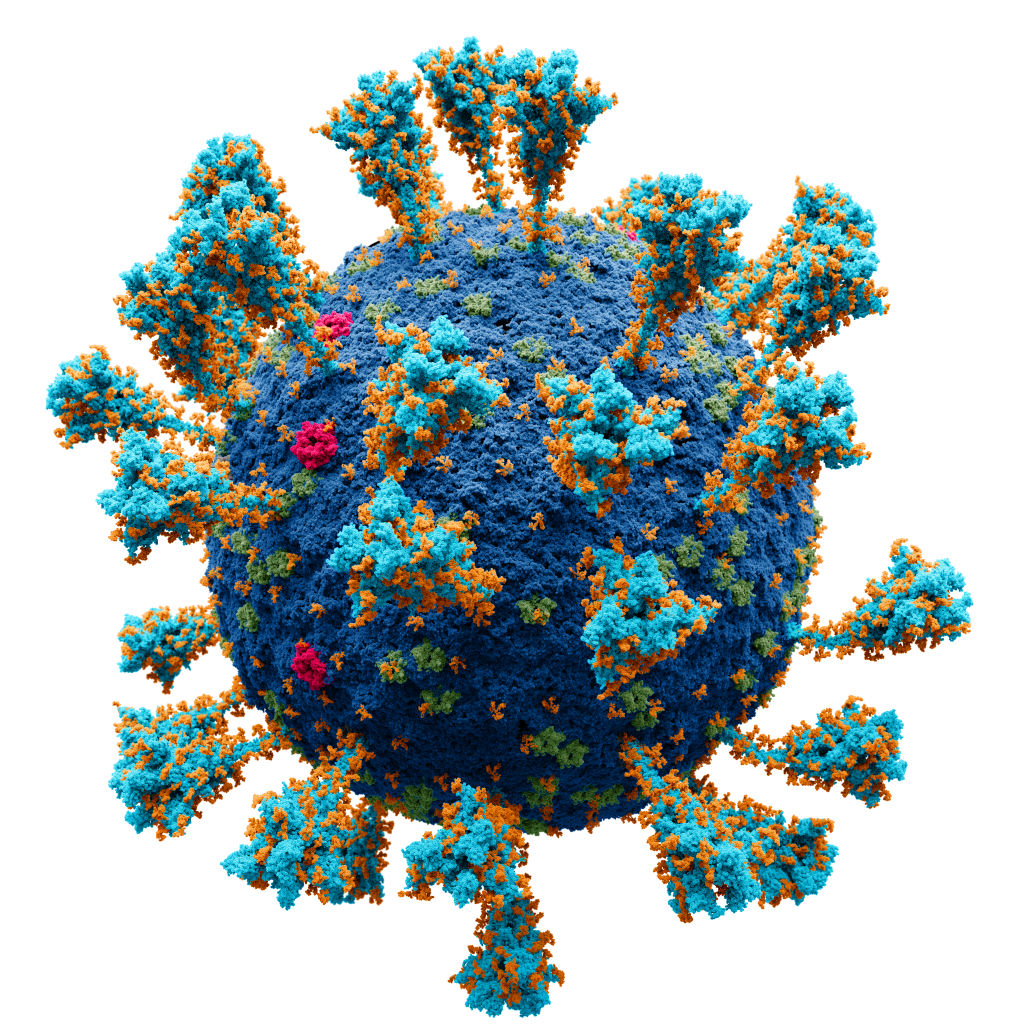

Brigitte Nerlich suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic became perhaps the first ‘global metaphor through which we, as a global population, can conceptualise almost every aspect of our lives’.11 A distinction can be made between global metaphors and universal metaphors, which are based on universal sensory experiences (ANGER IS HEAT is found across cultures, for example). Global metaphors, rather, are defined by acquired knowledge, and learned patterns of behaviour. Seen through this lens, the political cartoons described above can be regarded as global metaphors wielded to bring new, globally held understandings to bear on nonuniversal experiences.

Cancer Cells and Cabaret

The communication of scientific ideas is often highly metaphorical.12 That metaphor, a phenomenon traditionally associated with the arts, is so central to our understanding of scientific phenomenon such as pandemics, speaks to how the sciences and humanities are inextricably linked through language, and opens up space for fruitful collaborations across disciplinary lines.

Et in Arcadia Ego, an installation by artist Charlotte Jarvis, saw her work with molecular geneticist Dr Hans Clevers to produce cancer cells from her own healthy cells:

‘Atop the earth sits a box – entirely mirrored, inside and out – creating an illusion of infinite space, within which my cancer sat housed in a petri dish’.13

In talking about the exhibition, Charlotte recalls a friend of hers who died from kidney cancer. Before he passed away, they discussed how the conflict metaphors against which cancer is often understood serve to entrench the idea that dying from cancer is ‘both the fault of the patient and the result of something “other” to their bodies’.14 The intention was for Et in Arcadia Ego was to challenge these notions, and foreground the fact that cancer is, in effect, our own cells, and has always been a part of us. With this framing in place, notions of fighting (and thus losing or winning) might have less weight compared with, for example, metaphors about coexisting with or managing cancer. Hans later recounted that his colleagues described the exhibition as driving home the idea that cancer is not just an abstraction—that the ‘real thing is never far away’.15

Contagion Cabaret, a 2017 performance exploring contagion through history, which included musical pieces, eye-witness accounts and interventions by practicing medical professionals, was adapted and broadcast for an audience who were living under lockdown conditions. The first shot of the Mistress of Ceremonies sees her stride across an empty field, wearing a wartime gas mask and holding a red balloon, towards a microphone. This first encounter is striking, and invites metaphoric interpretation. What does it mean for the pandemic to be understood both as a red balloon, and a wartime gasmask?

The gas mask could be said to evoke the PANDEMIC IS WAR metaphor, whilst the presence of the balloon suggests joy, a certain lightness. The contrast between the two objects speaks to the two sides of the pandemic. On the one hand, people were dying, and there was a palpable sense that we were on a war footing. On the other, it was a time of making sourdough bread, Zoom quizzes and Joe Wicks workouts.

The two objects also speak to how history has taught us that the conditions that cause pandemics are ever present, even during times of levity. This interpretation is reinforced when the Mistress of Ceremonies tells us that the play will present us with a ‘feast of disease…the tastiest morsels of plays past and present,’ and that ‘we have all been here before’.16

‘We have all been here before’ draws on the common TIME IS SPACE metaphor, which conceptualises particular times as particular points in space. Its manifestation here collapses the distinction between pandemics through time. Viruses are, in a sense, timeless, inevitable. They are always there, invisible and mutating—the next pandemic is likely in the post.

Both Et in Arcadia Ego and the Contagion Cabaret create moments of metaphorical potential—moments that highlight scientific realities, make the abstract tangible, and challenge existing frameworks of understanding.

When is a Pandemic also a Metaphor? Always!

Given how central metaphor is to how we conceptualise the world, it was inevitable that metaphor would play a pivotal role in our understanding of the COVID-19 pandemic. Just as ‘media and technologies of communication’ are not passive bystanders when it comes to the ‘making and management of epidemic outbreaks’, this metaphoric understanding does not flow one way.17 Having drawn on existing concepts to understand COVID-19, our understanding of COVID-19 became our understanding of the infected world around us too. Both during and post-pandemic times, paying attention to, and working creatively with, metaphor can lead us not only to new external insights, but also to the deep internal questioning of conventionalised modes of thought.

Dr Tom White

Dr Tom White is a Visiting Lecturer at Newman University and Student Experience Officer in the School of English, Drama and Creative Studies in the College of Arts and Law at the University of Birmingham. Dr White completed his PhD at the University of Birmingham with a creative-critical thesis which sought to use creative writing to investigate various strands of metaphor theory, and metaphor theory to investigate creative writing as a process.

- Lakoff, G. and Johnson, M. (1980) Metaphors We Live By. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (p.1) ↩︎

- Kövecses, Z. (2020). Extended Conceptual Metaphor Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (p.2) ↩︎

- Thibodeau, P. and Boroditsky L. (2011) Metaphors we think with: The role of metaphor in reasoning. PLoS One. 6(2):e16782. ↩︎

- Smith, D (2020) Trump talks himself up as ‘wartime president’ to lead America through a crisis. The Guardian. 22nd March. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/mar/22/trump-coronavirus-election-november-2020. (Accessed: 23rd April 2025). ↩︎

- Guliashvili, N. (2022). “Invader or Inhabitant?” – Competing Metaphors for the COVID-19 Pandemic. Health Communication, 38(10), pp. 2099–2105. ↩︎

- Semino, E. (2021). ‘Not soldiers but fire-fighters’–metaphors and Covid-19. Health Communication, 36(1), pp. 50–58. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Abdel-Raheem, A. (2021). Reality bites: How the pandemic has begun to shape the way we, metaphorically, see the world. Discourse & Society, 32(5), pp. 519-541. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Nerlich, B (2021) The coronavirus: A global metaphor. University of Nottingham Blogs. 14th May. Available at: https://blogs.nottingham.ac.uk/makingsciencepublic/2021/05/14/the-coronavirus-a-global-metaphor/. (Accessed: 23rd April 2025). ↩︎

- Taylor, C. and Dewsbury, B. (2018) On the Problem and Promise of Metaphor Use in Science and Science Communication. J Microbiol Biol Educ. 30;19(1):19.1.46. ↩︎

- Jarvis, C. and Clevers, H. Et in Arcadia Ego: Addressing Cancer, Death and Immortality Using Science. Leonardo 2017; 50 (2), pp.197–198. (p.198) ↩︎

- Ibid. (p. 197) ↩︎

- Ibid. (p. 198) ↩︎

- The Theatre Chipping Norton (2020) The Contagion Cabaret. Available at:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wjddFe_Gaxk.(Accessed: 23rd April 2025). ↩︎

- Media and Epidemics Project. https://mediaepidemics.com/the-project/ ↩︎