“Sickness in [Edith] Nesbit’s novel […] is a conduit to illustrate how the community ought to respond altruistically to suffering, revealing that health is as much a public concern as a private one.”

What are the main epidemics that your team focuses on?

I am a fifth-year honours student completing a Bachelor of Advanced Humanities at the University of Queensland, Australia, where I am studying an extended major in English Literature. I joined the UK Media and Epidemics team for a short period under the supervision of PI Melissa Dickson as a recipient of a 2025 Summer Research Scholarship from the University of Queensland, Australia. Our Summer Research team is focusing on the Influenza Epidemic in England which began in 1889, where we are studying the cultural and social impact this colloquially dubbed ‘Russian Flu’ had on the following two decades.

What have your key research question(s) been this month?

- How is influenza represented in literature directed towards a children’s audience, particularly the works of Edith Nesbit and popular magazines like The Boy’s Own and Girls Own Papers?

- What attitudes about transmission and the susceptibility of children to disease can be found in this literature?

- What does the presence and/or absence of influenza in this literature reveal about attitudes towards the epidemic and what adults believed children should know about the epidemic?

- Do children and adults have different responses to the epidemic?

- Is communication of the epidemic towards children affected by moral didacticism, particularly concerning personal hygiene?

- Is influenza viewed like another creation of modernity, like the locomotives in Nesbit’s The Railway Children (1905), and what message does this send to young readers about their future world?

Have you found any key differences between how the epidemic disease experiences of marginalised or minority individuals, and between those of the general population, have been communicated?

Although influenza only has one prominent appearance in Edith Nesbit’s The Railway Children (1905), concerns about the capacity of those affected by poverty to be able to care for themselves and their family run steadily through the novel. When the title characters’ mother falls ill with influenza, despite the doctor’s prescription of remedies, the children find they have no financial means to purchase any of them. It is only through the children taking the initiative in appealing to a wealthy and beneficent stranger that they manage to procure all they need to return their mother back to health.

This emphasis on a community-based response to illness in those most vulnerable is further seen when a signalman on the railway falls asleep at his post due to caring all night for his child who is ill with pneumonia. Although a disaster is averted, the inability of the railway company to accommodate their worker’s need to care of his family emphasises the knock-on effect of a lack of duty of care for their workers’ wellbeing. Sickness in Nesbit’s novel, therefore, is a conduit to illustrate how the community ought to respond altruistically to suffering, revealing that health is as much a public concern as a private one.1

To what extent have you found that differing technologies can change how epidemics have been communicated? Are there any particular technologies that you wish to highlight?

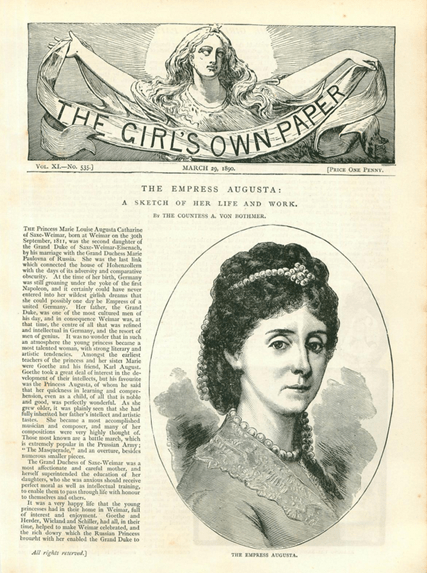

The proliferation of mass-produced magazines like The Boy’s Own and Girl’s Own Papers meant that more people of differing ages could get information cheaply and consistently. This meant that news of influenza and its victims, like Empress Augusta of Saxe-Weimar, wife of German Emperor William I, spread to a larger audience faster.

These magazines were also used as sources of popular medical advice either through direct responses to readers’ complaints or specialised articles from medical doctors. One of the most common pieces of advice is to the bathe daily, which was intertwined with the moral teaching that ‘Cleanliness is next to Godliness’. This dual messaging contributed to the distinction between the so-called ‘Great Unwashed’ and those wealthy enough to afford to bathe every day at home.2

What has been your most surprising finding while working on the Media and Epidemics project?

The most surprising thing I have found is perhaps the consistency with which Nesbit includes sickness in her stories as a plot device, especially as something that enables imagination and fantastical storytelling. This is completely different to how dirtiness and sickness is presented in the contemporary Boy’s Own and Girl’s Own Papers, where it is depicted as morally corrupt. In Harding’s Luck (1909), for instance, Nesbit uses fever as a device to enable time travel and consciousness to transfer into another life, with this slippage between the real and fantastical world being presented metaphorically as a feverish dream.

- Noimann, Chamutal. “‘Poke Your Finger into the Soft Round Dough’: The Absent Father and Political Reform in Edith Nesbit’s The Railway Children.” Children’s Literature Association Quarterly, vol. 30, no. 4, 2006, pp. 368-85. ↩︎

- Crook, Tom. “Personal Hygiene: Cleanliness, Class, and the Habitual Self.” In Governing Systems: Modernity and the Making of Public Health in England, 1830-1910, U California P, 2016, pp. 245-85. ↩︎