Brochure disseminated by the Romanian Red Cross in 1963.

Research on epidemics and technologies of communication is still scarce in Romania. The Romanian team focus is on documenting and understanding the socialist policies and practices of public health communications, which were applied by the Romanian authoritarian regimes after the second world war in order to prevent or to limit epidemics.

My own work within the team explores what mass communication looked like and how it was carried out by an unpopular dictatorial regime, asking was it persuasive? Was it violent? Was it funny? One educational campaign that was at times all three was the Romanian National Society of the Red Cross.

The Red Cross, an organization with large competencies in mass sanitary education and public health, was set up in Romania in 1876 and suffered through the socialist transformations of the post-second world war period. The government of the day used it as an instrument for mass-education and sanitary instruction across institutions, from schools to factories and universities. Naturally, its education campaigns targeted different ages and social and professional categories but they typically consisted of lectures, exhibitions, leaflets, handouts, brochures, magazines.

An Opportunity for Storytelling

In the 50s and early 60s, television was not a mass-product in Romania, and radios were available mostly in the cities. Leaflets and brochures were, therefore, very handy and practical for disseminating information and education. They were functional and informative. Some used storytelling to educate especially the villagers about the role and necessity of doctors and hospitals. Others used lyrics to educate the children about the importance of healthy habits.

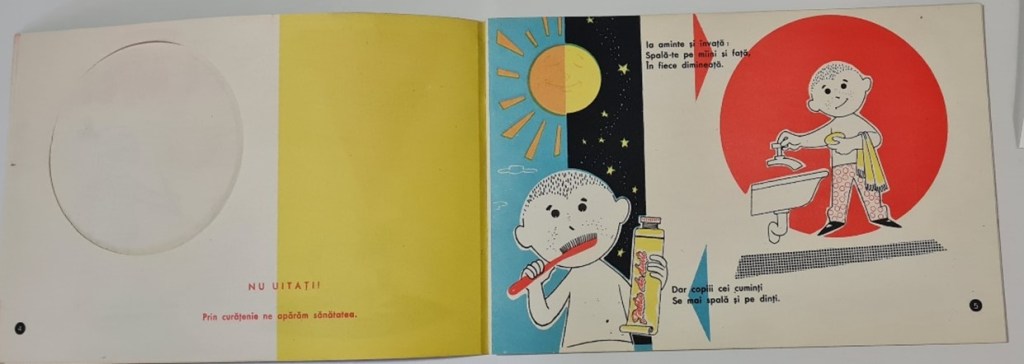

One such brochure dedicated to children was disseminated by the Romanian Red Cross in 1963. Written by a doctor who signed only his initials, it contained short, simple rhymes for children on how to keep healthy, alongside brief practical advice for parents on how to keep their children safe. Its intention was to be simple, colourful and funny, attractive and interesting for infants.

The Power of Imagery: From Anthropomorphism to Threat

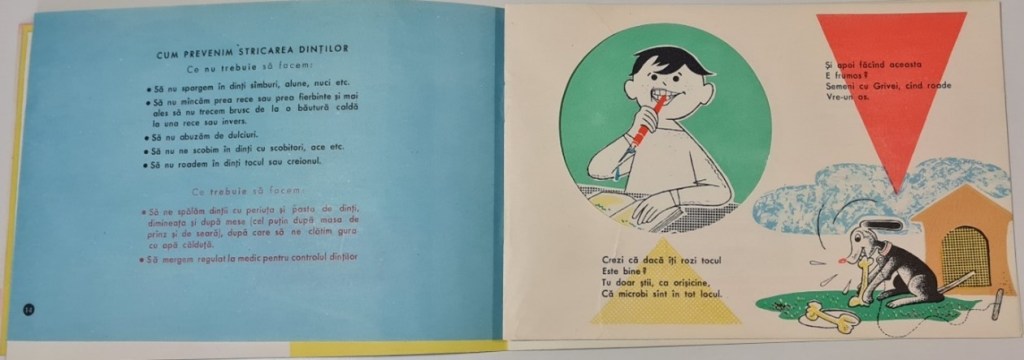

Image-centred, the brochure uses anthropomorphic animals and objects, represented in different relations to children, in order to explain healthy habits like washing daily (as a cat does), or responding to the parents’ calling for meals (as chicks do when the hatching hen calls them), cleaning teeth (like birds who clean their beaks after eating), and not chewing their pens (which makes them look like dogs).

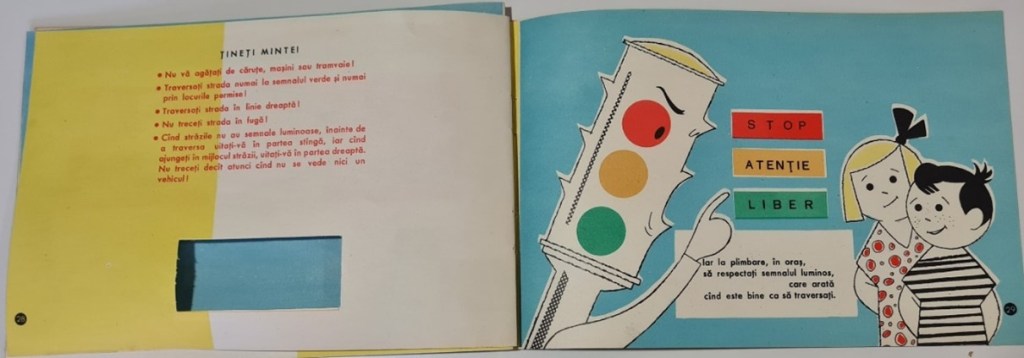

But the seemingly harmless and playful tone of the text gradually shifts into the imperative as the advice switches from aspects of good health to “bad behaviour”, like playing with fire, using poisonous substances, and crossing the street illegally. Frivolity turns into violence in an apotheotic ending, in which the traffic light throws a very angry and threatening look to two smiling children who try to cross the street. The drawing is displayed against a forced rhyme announcing to the children that they ought to respect the traffic lights when they walk on the streets. The traffic light is a figure of authority, akin to the parent or the Romanian militia, either of which would have the “right” and the habit to exert such violence on children.

Gender as a Tool

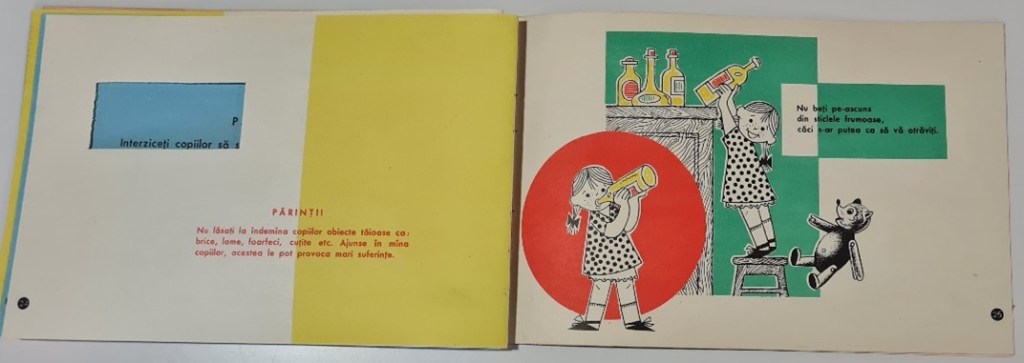

The children in this brochure are, for the most part, young boys, in a cognitive schema that relates all important activity and movement in the public sphere to men only. There is only one instance in which the child is imagined as a girl, when the text warns about ingesting poisonous substances that are bottled in colourful, “beautiful” packages. There are two main reasons for this: girls are future household keepers and cleaners and therefore need to learn how to handle these objects safely, and girls are seen as more likely to be attracted to “colourful” bits and pieces and therefore more in danger of ingesting domestic chemical substances. Girls are present only to learn the rules of managing a household.

Context is Key

Materials like this brochure convey not only health advice, but also social and political expectations relating to gender roles and compliance. Fun can easily provoke fury in such brochures, and violence is the main form of persuasion.

It is important to understand that such artefacts are never “above” or beyond the context in which they were produced. They are embedded in the political and social practices of their context; they encapsulate them, and they carry their message across time. Even more importantly, they contribute to their perpetuation.

Dalia Bathory

Romanian Team